Mast Cell Tumors

Skin tumors are the most common form of mast cell tumor (MCT), and they exhibit many different characteristics such as wart-like nodules, soft lumps below the skin, or an ulcerated skin mass. The appearance of MCTs is extremely variable since they may swell and shrink unpredictably. In addition, they are often mistaken for an insect bite, wart, or a fatty mass below the skin called a lipoma. Although mast cell tumors often appear later in a dog’s life, it is not impossible for animals less than a year-old to develop this type of cancer. Diagnosis is initiated using fine needle aspiration, and if an abnormal number of mast cells is present, a surgical biopsy will provide a more definitive identification of the MCT grade and stage of development.1

Although the exact cause of MCT is not known, there are a number of risk factors that contribute to the disease. In addition to environmental contributors, several mutations are involved in MCT development. For example, mutation of the mast cell’s c-kit gene results in excessive expression of c-KIT protein, thus increasing the replication and division of these cells. Two other mutations contributing to MCT development occur in genes coding for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and/or platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR).3 In fact, promising new treatment choices are becoming available as chemotherapeutics which target and inhibit these genes are developed.

It is important to attend to your pet’s health since early detection, surgical removal, and regular evaluations increase the probability that your pet will live a normal and comfortable life. If the MCT is allowed to progress and spread, the prognosis is poor and will depend on the grade and stage of tumor development. Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, and possibly radiation for tumors in difficult locations.

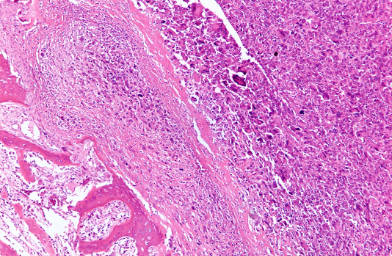

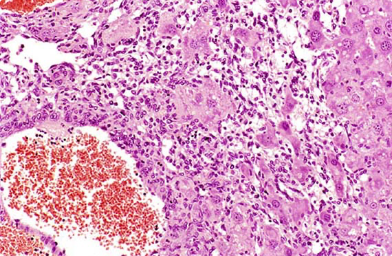

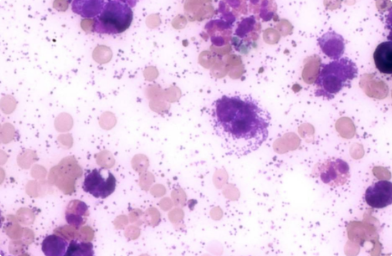

Mast cells are derived from bone marrow and play important roles in the body’s defense system. Under the microscope, several types of dark granules can be seen. These granules contain several biologically active compounds, such as histamine and heparin, that mediate allergic reactions and inflammation.1 For example, when exposed to allergens, mast cells undergo a process of degranulation and histamine release. Histamine exposure causes itchiness, sneezing and runny nose, symptoms well-known to people with allergies; however, allergic release is minor compared to the excessive amount of histamine released from rapidly growing mast cell tumors (MCT) which are undergoing mass degranulation. In fact, this massive release of histamine can result in full-body effects such as anaphylactic shock which is life-threatening.2.

Mast cells reside throughout the body, but excessive growth of mast cells and development of mast cell tumors is most commonly detected in the skin, lungs, nose and mouth. The most common site for MCT development is skin where their behavior ranges from being non-cancerous (benign) to highly malignant. If the entire body is affected by abnormal mast cell proliferation, the disease is called mastocytosis.3

Mast cells release several biologically active chemicals such as histamine and heparin, and excessive release of these compounds from rapidly growing MCTs can be very damaging to the body. The highly variable MCT histological pattern and the level of aggressiveness or grade of the tumor is used to provide a prognosis for the animal and to predict the potential risk for metastasis. If the MCT does spread, the regional lymph nodes are the first site of relocation followed by movement to the spleen and liver.3

Mast cell tumors are the most common type of skin cancer found in dogs and account for approximately 14 to 21% of all diagnosed skin tumors in these animals.4 MCTs are often seen as solitary lumps or masses in or underneath the skin. Occasionally, dogs can have multiple MCT masses. MCTs can also appear as wart-like nodules, ulcerated skin masses, or may even resemble insect bites. These tumors usually affect older dogs (average age of 8 years), but MCTs in puppies as young as 4 months have been recorded.1 Approximately 50% of MCTs are found on the trunk and the area between the anus and vulva (females) or anus and scrotum (males); 40% are located along the extremities such as the paw; and 10% are discovered along the neck and head.3

As with most canine cancers, the risk for developing MCTs is higher in particular breeds such as Beagles, Boston terriers, Boxers, Bullmastiffs, Bull terriers, Cocker spaniels, Fox Terriers, Golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers, Schnauzers, Staffordshire terriers, and Weimaraners.4

Symptoms

The initial appearance of a MCT is accompanied by redness and swelling around the tumor due to localized release of histamine, proteolytic enzymes and vasodilatory substances. Release of histamine may cause swelling and bruising around the tumor which make MCTs appear as if they are continuously swelling and shrinking.4 Moreover, since cancerous mast cells can release significantly more histamine compared to normal mast cells, they are particularly damaging to the stomach lining where histamine stimulates acid production, Release of these compounds is associated with ulcers and additional symptoms such as vomiting, loss of appetite, bloody stool, low red blood cell counts, and abdominal pain.4

The following summary includes a few of the more common symptoms of MCTs:1

- A mass or lesion appears on skin or subcutaneous tissue at any location.

- A region of inflammation surrounds the tumor.

- Individual tumor undergoes swelling and shrinking: exhibits variable size.

- Some tumors are ulcerated; others are covered with hair.

- Redness, bruising and fluid buildup (edema) can occur, and may worsen with manipulation or scratching

- Enlarged lymph nodes can appear near areas of tumor involvement.

- Loss of appetite, vomiting or diarrhea

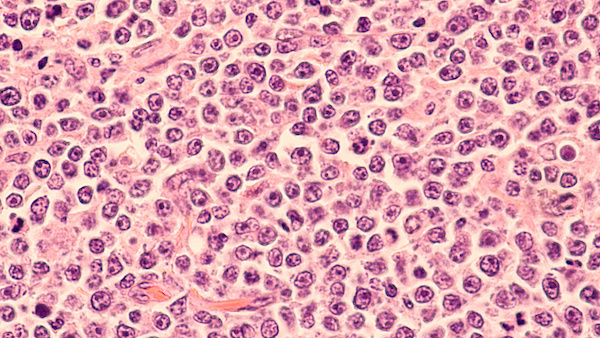

Canine mast cell tumors are also divided into grades which reflect the extent of differentiation. The extent of differentiation is used to determine how different the mast tumor cells are from normal cells. The closer the mast cell is to a normal cell, the more differentiated it is. If the mast cell is undeveloped and rapidly dividing, it has failed to differentiate and is more likely to invade other tissues. The higher grade signifies that the cells are less differentiated and the risk for malignancy is higher.7 Mast cell tumors located on limbs, head and neck are more likely to have a more favorable prognosis compared to those found on the trunk or groin.

Grading6

Grade 1

Mast cells at this level are well-differentiated and are associated with a survival rate of at least 93% post-surgery (> 1500 days). These cells are not aggressive and rarely metastasize.

Grade 2

These cells are moderately differentiated with a 47% survival rate post-surgery (> 1500 days). They are more aggressive than grade 1; however, 50% of the mast cell tumors do not spread after treatment. Recurrence may be detected within 10 months. If they do not recur during this period, the likelihood of relapse over the next five years is low.

Grade 3

Mast cells are poorly differentiated with a 6% survival rate post-surgery. This MCT has a high metastasis rate and is likely to spread to regional lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and bone marrow.4 Unfortunately, a very guarded prognosis accompanies grade 3 MCTs and 97% of grade 3 tumors cause death within one year of onset.

The cause of mast cell tumors is not straightforward. Similar to most cancers, there is no single cause and most growths result from a complex mixture of risks which include environmental as well as genetic factors. Mutations in genes known to code for receptor tyrosine kinases such as c-KIT, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) have been identified as contributors to MCT development and are currently being studied as potential drug targets for chemotherapeutic agents.3

Mast cell tumors are often mistaken as an insect bite, a wart, or a simple allergic reaction such as a hive. Skin abnormalities should be promptly evaluated by your veterinarian since early detection is the key to a positive outcome. Your veterinarian will ask you to provide a thorough history of your dog’s health, especially the symptoms you have observed with regard to the growth. Following a physical examination, your veterinarian will look closely at the mass or nodule and proceed with a fine needle aspirate. This simple procedure is routine and allows fluid and cells to be suctioned from the mass. Since mast cells contain numerous granules that can be stained and evaluated microscopically, the initial diagnosis is fairly rapid. However, mast cell tumors can take on a variety of appearances and before removing any skin lump, the tumor should be thoroughly evaluated in order to distinguish mast cells from other malignant tumors. Most often your veterinarian will take the steps outlined below.1

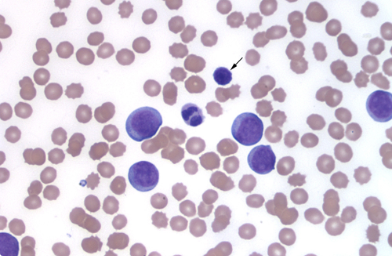

Fine Needle Aspirates

This is one of the most important steps of the examination. It is used in almost all cases and can be used to diagnose MCT as well as provide a measure of its potential spread to lymph nodes and other internal organs. It is a minimally invasive technique in which a needle is inserted into the tumor and suction is applied. Expectedly, the procedure is quick and painless. The aspirate can be placed on a microscope slide for histological evaluation. This procedure allows the tumor to be typed and graded. The unpredictable behavior of mast cells mayt complicate confirmation of the tumor type and grade. In such cases, the following additional tests can be performed for confirmation.4

Blood and Urine

samples are taken and evaluated for metabolites. This information is used to assess organ function, identify concurrent disease such as liver or kidney, and detect whether mast cells are circulating in the blood.

Abdominal ultrasound

This test collects information about the size, shape, and texture of abdominal organs which might provide evidence that the MCT has spread.

Chest Radiographs

X-ray images are used to evaluate heart and lungs in order to check for concurrent diseases and to determine if MCT has spread. This information allows the veterinarian to provide surgical recommendations and to help you understand your pet’s long-term prognosis.

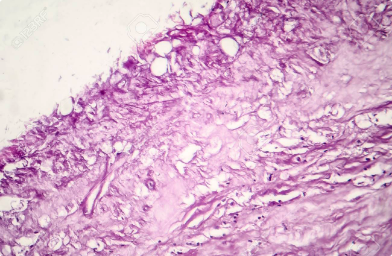

Tissue Biopsy

Surgical biopsy provides for a more detailed microscopic evaluation of the MCT in order to confirm the diagnosis and to establish the stage of differentiation and tumor grade. Cell proliferation analysis, which is reported as the proliferation index, measures the expression of proteins involved in cell growth and division. For example, the relative number of Ki67-, PCNA-, or AgNOR-positive cells can be used to calculate the proliferation index. Increased expression of these genes indicates tumor growth.6

Computerized Tomography (CT) Scan

This scan collects a series of X-rays taken from different sites around the body and uses computer processing to generate cross-sectional images (slices) of bones, blood vessels, and soft tissues. CT identifies the precise location and size of MCTs. The results are valuable especially for planning surgery and/or radiation therapy.4

Surgery

If the MCT can be completely removed and shows no sign of spreading, surgery is the ideal treatment. The surgical removal of the tumor mass and normal tissue surrounding the tumor ensures that cancer cells are not left behind. Surgery is followed by a histologic evaluation to confirm that no cancer cells are present in the healthy tissue surrounding the mass (clean margins). Be sure that your dog is scheduled for regular check-ups.

Chemotherapy

Depending on the veterinarian’s assessment, you could also choose chemotherapy to prevent or minimize the risk for recurrence or metastasis. Veterinary oncologists are not in full agreement with regard to the potential benefit of chemotherapy after successful removal of grade I tumors; however, if histologic evaluation confirms the presence of cancer cells in the healthy tissue surrounding the removed tumor (dirty margins) or if it has moved to local lymph nodes as in grade II tumors, then additional surgical removal and/or chemotherapy may be recommended as outlined below:.7

- A drug commonly used after removal of grade 1 or 2 MCTs is prednisone, a cortisone derivative. This steroid is well tolerated by dogs and is usually administered for approximately six months following surgery. If no new tumors are detected, your dog can be safely weaned off of this drug.

- For recurrent tumors or for those that cannot be surgically removed, a combination of both prednisone and vinblastine has been shown to be effective in controlling tumor growth and spread for weeks, months, or more. This combination is usually well-tolerated and can extend your dog’s quality of life.

- Additional drug choices are often recommended for dogs where MCTs have become resistant to other treatments; these may include Cytoxan or Lomustine.

- Implanting steroids and delivering radiation into the tumor bed during surgery has also been shown to increase long-term remissions and survival [5].

If the MCT has been assigned grade III and has spread, chemotherapy is the best choice for treating the metastasis. Recently, the arsenal of anti-cancer therapies for canine mast cell tumors has expanded to targeted chemotherapies which are much more likely to inhibit tumor growth.3

- Palladia specifically inhibits c-Kit, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFR β) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2), molecular targets known to mediate cancer growth.

- Masitinib, another targeted therapy, is not only a specific inhibitor of c-Kit and PDGFR α and β, but also inhibits the tyrosine kinase protein known as Lyn

Whatever you and your veterinarian choose, always monitor your pet for possible tumor recurrence or metastasis since early detection is the key to positive outcomes.

Medical Management of MCT

In addition to treatment of the cancer, medications may also be used to alleviate secondary effects of the mast cell tumors which may include steroids, anti-histamines, histamine blockers, and/or pain killers. These medications help to reduce the inflammation and associated side effects of MCTs prior to surgery or can be used for palliative care.8,9

Radiation Therapy

For years, conventionally fractionated radiation therapy (CFRT) was used alone or in conjunction with surgery for treatment of tumors that were difficult to reach such as in the paw. Radiation is often used as a treatment for incompletely excised tumors; however, it should be understood that CFRT can sometimes damage normal and healthy tissue around the tumor. A more successful approach has been developed using stereotactic radiation (SRS/SRT).9

SRS/SRT is a newer type of radiation therapy which delivers high doses of radiation with sub-millimeter precision. The advantage of this approach is that it can do maximum damage to the tumor while causing minimal collateral damage to healthy tissues. This therapy is not only more effective, but can be applied in 1-3 sessions which reduces your pet’s exposure to anesthesia and lessens the number of trips for the owner.9

As with any cancer, the earlier it is diagnosed and treated, the more successful the treatment. Prognosis differs depending on the MCT grade and completeness of surgical excision. The location is also very important; for example, predicted outcomes for tumor growth in internal organs is usually less favorable compared to tumor growth in skin. The prognosis for completely excised grade I or grade II tumors with clean margins is excellent. For incompletely removed grade I or grade II tumors followed by radiation therapy, the outcome is also exceptionally good with approximately 90 to 95% of dogs showing no signs of recurrence within three years of radiation.8

The expected outcome for dogs with grade III mast cell tumors is not as positive since local recurrence and/or spread is likely. In this case, it is common to follow the initial surgery with chemotherapy. Drugs such as Lomustine and Vinblastine are often added to the treatment protocol.8