Osteosarcoma

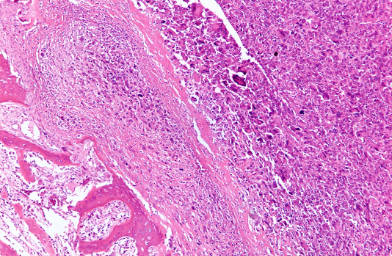

There are a variety of canine bone cancers, however, osteosarcoma is by far the most common and represents about 85% of the skeletal malignancies in dogs. This form of bone cancer is found mainly in the limb bones which are part of the appendicular skeleton, but it can also occur in bones of the spine, skull, rib and pelvis which comprise the axial skeleton. Although there is a hereditary basis for osteosarcoma based on breed and familial incidence, the major predisposing factor is size of the dog, with large and giant breeds being particularly susceptible to the disease. In addition, males are more likely to develop the disease compared to females. Osteosarcoma has been detected in dogs, cats and humans; however, dogs are four times more likely to develop this type of bone cancer compared to humans.

Following a full collection and interpretation of diagnostic tests which may include X-rays, blood tests, and bone scans, your veterinarian will suggest various treatment approaches. Treatment of canine osteosarcoma has two goals—relief from pain and curative intent. Treating the pain successfully will allow a dog to live comfortably and extend life expectancy by increasing the dog’s comfort level. Options for treatment include aggressive modes of therapy such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Most dogs recover quite well from these procedures and are running and playing in a very short time. However, there is no ‘best’ way to treat bone cancer. Hopefully, the information presented below will help you understand your pet’s cancer and allow you and your veterinarian to find the right option for you and your pet.

Osteosarcoma is a very aggressive cancer of the bone. Its malignant tumors most often originate in limb bones of the appendicular skeleton near the border of shoulder, wrist or knee, 3 particularly in large and giant breeds of dogs. Osteosarcoma can also occur within the bones of the axial skeleton such as the skull, spine or ribs, however, tumors at these sites are less common, grow much more slowly, and are less likely to spread to other parts of the body.10 This spreading is called metastasis.

Osteosarcoma spreads most rapidly into the lungs and other bones.7 However, unlike many metastatic cancers, osteosarcoma spreads to the lymph nodes in only 4% of cases. Unfortunately, at the time of diagnosis, approximately 90% of dogs with this disease already have metastasis but the new tumors are still microscopic and not detected with imaging.6

As the osteosarcoma develops and grows outward it begins to destroy the bone and becomes increasingly painful. You may notice a reluctance for your pet to walk or play and they begin to show signs of labored breathing, cough, and loss of appetite. Dogs suffering from osteosarcoma appear to tire easily and a mass or painful inflammation may surround the tumor site. Lameness can occur suddenly or may go from intermittent to constant over 1 to 3 months. 55 Swelling becomes more obvious as the tumor grows and normal bone is replaced by tumorous bone which is weak and can break with minor injury.3 This type of broken bone is called a pathologic fracture since it will not heal and cannot be repaired. This ultimately becomes the finding that confirms diagnosis.5

Appendicular

Appendicular osteosarcoma is an aggressive and invasive cancer that destroys bone locally.11 If osteosarcoma is affecting your dog’s limb, you may have observed a local firm swelling, particularly near joints. You may also have noticed that your dog has developed a lameness which is persistent and does not resolve with painkillers.1

Osteosarcoma is a painful condition, so there may be signs of restlessness. However, some dogs are extremely brave and hide pain remarkably well. If you suspect a change in your dog’s behavior, keep an eye out for subtle behavioral changes that only you might notice such as loss of appetite, shaking or shivering, change in demeanor and reduction in activity levels. Keep a daily diary if you begin to observe these changes. Since the cancer degrades bone architecture, it weakens the bone and may result pathologic fractures.1 Pathologic fractures will not heal and there is no point in putting on casts or attempting surgical stabilization.5

Appendicular osteosarcoma is highly metastatic which complicates diagnosis and treatment. It moves rapidly throughout the body and is found most often in the lungs with a lower frequency in distant bones and other sites. Unfortunately, this early and rapid rate of spreading results in microscopic metastatic tumors which are called micrometastases. Less than 15% of dogs have radiographically detectable pulmonary metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis, 85-90% of patients will go on to develop gross metastasis despite effective control of the primary bone tumor.11

Axial

Osteosarcoma that occurs in the axial skeleton, which includes skull, ribs, vertebrae and pelvis, most often develops in small, middle-aged dogs. Compared to growths in the appendicular skeleton, tumors developing in the axial skeleton grow much more slowly; however, this leads to a more insidious course for the disease. The tumor may be present for as long as two years before it is formally diagnosed. An exception is osteosarcoma of the rib, which tends to be more aggressive than other axial osteosarcomas.3

Osteosarcoma in the mouth may present as very bad breath and eventually the sight of blood in the food or water bowl may lead to your discovery of a visible mass near the teeth or gums. If your pet has osteosarcoma of the skull bones, the tumor may cause changes in their facial appearance and symmetry, or grow into the brain cavity possibly causing seizures. Spinal osteosarcoma may compress the spinal cord or nerves which may cause your dog to have difficulty in walking, partially or even completely. A firm fixed swelling beneath the skin over the rib cage, often about two-thirds down the length of the rib, indicates rib osteosarcoma.1

General Symptoms

The most common symptom associated with appendicular osteosarcoma is lameness.10 Lameness may develop suddenly, especially after vigorous activity, or may develop slowly. Depending on the location of the tumor, a swelling or mass is often seen in the affected limb.9 Although mild at the onset, lameness caused by osteosarcoma progresses over time, and the pain level can morph quickly from mild to severe if the diseased bone suddenly develops a crack or a full, bony break.10 Disruption of the bone’s vascular connective tissue, or periosteum, which normally covers and protects the bone can also cause visible pain in your pet which again leads to lameness, especially if there has been a history of mild trauma before the onset. This disruption of the periosteum ultimately increases your pet’s susceptibility to frequent fractures.

Symptoms associated with axial skeletal osteosarcoma are site-dependent and include the following:12

- Localized swelling.

- Dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing).

- Exophthalmos (bulging of the eye forward out of the orbit).

- Pain on opening of mouth.

- Facial deformity and nasal discharge and in abnormal increase in sensitivity to stimuli of the senses).

Increased pain can also cause problems such as irritability, aggression, loss of appetite, weight loss, whimpering, sleeplessness, and reluctance to exercise.

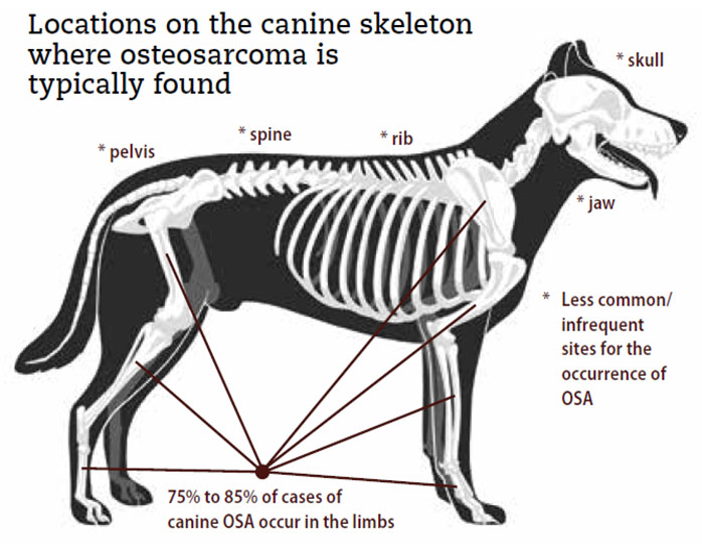

The causes of osteosarcoma in dogs are not well understood. However, since osteosarcoma tumors are frequently found near growth plates, it is speculated that factors affecting growth rates, such as diets that promote rapid growth in puppies, may increase the susceptibility at these sites during adulthood. Osteosarcoma tumors are most likely to occur in limbs, particularly forelimbs which bear most of the body weight and these appendicular tumors represent 75 to 85% of skeletal malignancies compared to the less-common axial cancer which occurs in other bones such as ribs and skull.3

Other factors like ionizing radiation, chemical carcinogens, and foreign bodies such as metal implants, internal fixators, bullets, and bone transplants increase the risk for osteosarcoma. Pre-existing skeletal anomalies, often occurring at sites of healed fractures, are also capable of triggering the disease.12

A number of traits seem to influence the development of osteosarcomas; including heredity, breed, rate of growth, and sex. For example, studies showed that in Scottish deerhounds, which have very low variability in genetic factors, approximately 70% of the osteosarcoma cases were a result of heritable factors.23 As mentioned earlier, there are certain breeds that have a higher incidence of osteosarcoma, and the rapid rate of growth in the large and giant breeds is especially influential as a predisposing factor. This is further supported by the finding that smaller breed dogs, which grow much more slowly during development, have a significantly reduced prevalence of canine osteosarcoma.

In fact, the major predisposing factor is the size of the dog and large breeds such as the Rottweiler, Saint Bernard, Great Dane, Irish Setter, Doberman Pinscher, German Shepherd and Golden Retriever are at the highest risk for osteosarcoma.7 Although dogs of any age can potentially develop this disease, larger breeds tend to develop tumors at younger ages. Dogs under 30 pounds account for less than 5% of osteosarcoma cases, and in these dogs, the cancer typically affects the axial skeleton, which includes bones of the skull, vertebral column, ribs, and pelvis.

In addition, studies show that biological sex influences the susceptibility to osteosarcoma since males are much more likely to develop this disease. It also appears that neutering before one year of age also predisposes certain dogs to osteosarcoma and disease risk becomes 65% higher for castrated males and 34% higher for spayed females. However, this risk factor has only been studied in a few of the large breeds such as the Rottweiler24 and Golden retriever.25 These studies suggest that sex hormones secreted during bone growth and development have a protective effect against the disease in particular dogs.

Thus, factors that can increase risk include the following:7

- Rapid growth in large and giant breed puppies.

- Biological sex: males are at a 20 to 50 percent higher risk.

- Placement of metallic implants in the bone to repair fractures.

- Spaying or neutering at an early age.

- Trauma to the bones, especially blunt bone injuries.

Diagnosis of canine osteosarcoma is initiated with a complete orthopedic and neurologic examination, a physical examination, and regional x-rays.7 A tentative imaging diagnosis can be made based on these radiographic findings and clinical signs, but a definitive diagnosis can only be made through tissue sampling of the affected bone. This sampling is usually obtained using core bone biopsies or aspiration of the tumor using an ultrasound-guided needle. It is also possible to remove a sample from the affected limb after amputation.16 Sampling of the affected bone is used to identify the type of tumor, although some oncologists claim that biopsy is not needed if the radiographs show an obvious bone tumor. Usually, if there is doubt about the lesion on the radiographs, a bone biopsy or fine-needle aspirate of suspicious areas will help to confirm the diagnosis.7

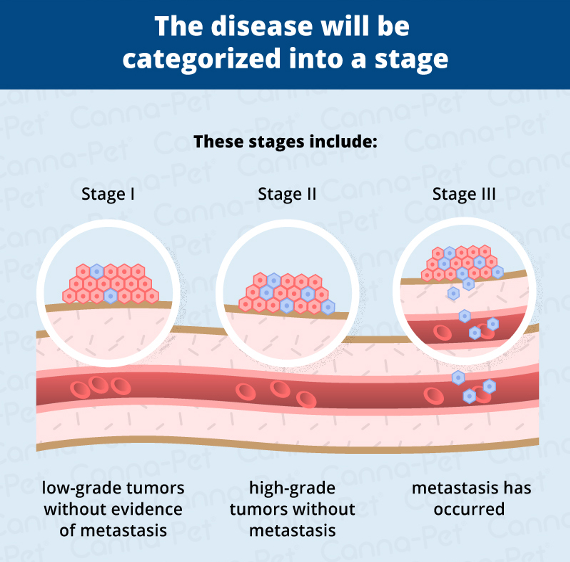

These procedures are painful and require sedation or anesthesia. Unfortunately, there is often a large amount of inflammation associated with this type of tumor making it difficult to obtain an adequate sample of the actual tumor cells. To minimize the spread of the tumor cells along the biopsy pathway, small samples are taken. Even though bone biopsies are performed with the utmost care, this procedure always carries a small risk of fracturing the bone. Since many dogs become even more lame and experience serious pain after a bone biopsy, a fine-needle aspirate is the preferred method. As with most medical procedures, the biopsy does not always yield an unequivocal diagnosis, and blood tests and chest X-rays are usually performed as well. Since up to 90% of osteosarcoma tumors have spread to the lungs by the time the disease is diagnosed, computed tomography (CT) scans and a magnetic resonance image (MRI) are used to better assess lung involvement and to evaluate a pet’s overall condition in more detail. During diagnosis, the disease will be categorized as stage I — low-grade tumors without evidence of metastasis, stage II — high-grade tumors without metastasis, or stage III — metastasis has occurred).7

In summary, a presumptive diagnosis of osteosarcoma is made specific following the collection and interpretation of tumor characteristics, history, and clinical presentation.11. In addition, your veterinarian will use X-rays to view the mass from various angles and other tests such as biopsies, blood tests, bone scans, and CAT scans to verify the diagnosis.2 The tools used for diagnostic purposes are more fully described below:5,7,21

Radiographs (X-rays)

One of the first steps in evaluating a persistent lameness is radiography (x-rays). Bone tumors are tender so it is usually clear what part of the limb should be radiographed. Osteosarcoma exhibits some unique characteristics including those described below:

- Characteristic lytic or “moth-eaten” appearance. The moth-eaten appearance of the bone consists of multiple scattered holes that vary in size and seem to arise separately. These scattered holes coalesce to form larger areas of bone destruction in a specific location.

- Sunburst pattern shown as a corona effect owing to the tumor’s outward growth pushing more normal outer bone up and away.

- Pathologic fracture.

Although most bone tumors are readily identified using radiography alone, X-rays taken of the affected limb can also be used to rule out any other problems such as fracture or infection. They allow the veterinarian to ascertain the extent of cancer infiltration into the bone and neighboring joints as well as the extent of tumor spread to other parts of the body, specifically the chest and lungs. Since there are other conditions that can mimic the appearance of a bone tumor, one of the confirming tests listed below is usually ordered to verify the diagnosis.

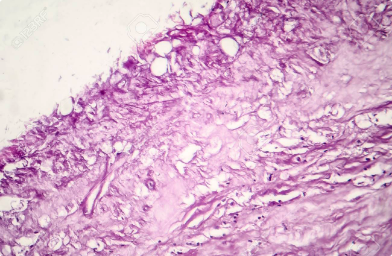

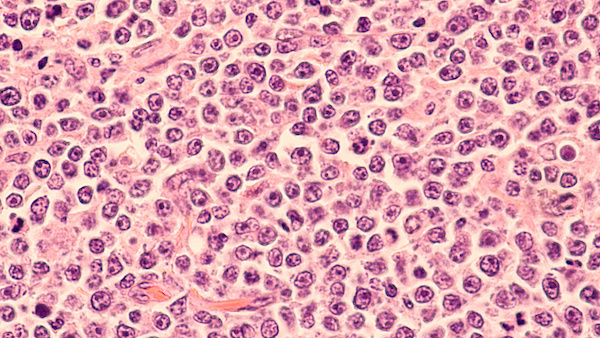

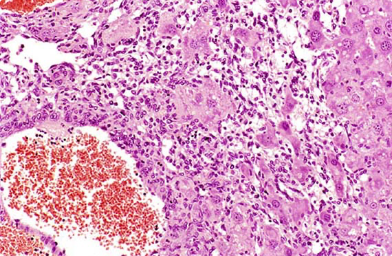

Bone biopsy

A small piece of bone is harvested surgically. The bone is preserved, sectioned, and examined under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis of osteosarcoma. There are several difficulties associated with this diagnostic. Sometimes bone tumor cells are surrounded by an area of bone inflammation and it may be difficult to get a representative sample. In addition, the tiny hole that results when a core of bone is removed can create a weak spot and the bone can actually break. Even if the procedure goes well, there is often increased pain and lameness for patients afterwards and as mentioned previously, most specialists have switched to needle aspiration for diagnosis.

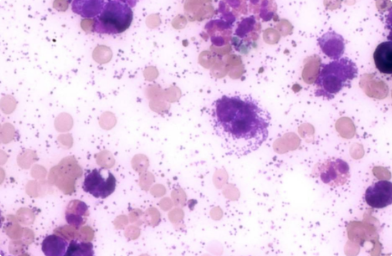

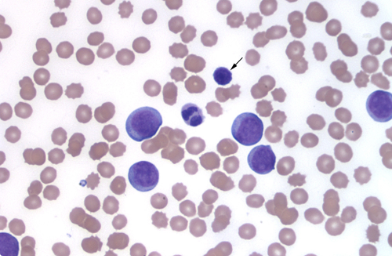

Needle Aspirate

Under sedation, a fine needle is pushed through a thin defect in the bone wall to collect cells for microscopic examination and confirmation of the cancer diagnosis. A full core of bone is not removed, just a sampling of cells. This is usually sufficient to confirm osteosarcoma. But sometimes insufficient material is obtained, and while under general anesthesia additional bone tissue is removed and examined in order to confirm malignancy. It is not always necessary to biopsy bone lesions ahead of treatment.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT takes virtual ‘slices’ through organs by providing ‘cross-sectional’ imaging. It is a much more advanced imaging technique compared to X-rays, capable of detecting more subtle changes in bones and lung. CT can also be used to reconstruct bone tumors in 3D to help your oncology clinician make decisions about whether or not it is possible to save the leg which is called ‘limb-sparing’. To diagnose osteosarcoma, your veterinarian will typically follow these steps:

- Vet will take an X-ray and perform a physical and orthopedic examination to rule out other causes of lameness.

- Problem areas identified on the X-ray will be biopsied to obtain a definitive diagnosis and determine the best treatment plan for your dog.

- Chest X-rays or a CT scan, blood tests, and a urinalysis will also be performed to assess your dog’s overall health and determine if the cancer has spread. Sadly, the tumor will have already metastasized at the time of diagnosis in 90-95% of dogs. As mentioned previously, osteosarcoma most commonly spreads to the lungs.

Advanced CT imaging is often recommended for osteosarcoma tumors of the limbs because it allows the veterinary surgeon to determine if surgery is possible and to assess the extent of surgical intervention necessary to achieve a favorable outcome.4

Canine patients are usually euthanized due to pain in the affected bone. However, treating the pain successfully will allow a dog to live comfortably and extend life expectancy. Options for treatment include combining aggressive modes of therapy such as surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Treatment of canine osteosarcoma has one of two goals—relief of pain and lameness or curative intent.3 There are two common ways to address the pain— amputating the limb and palliative radiotherapy which is usually combined with periodic bisphosphonate infusion treatments.5 Most dogs recover quite well from these procedures and are running and playing in a very short time. However, there is no ‘best’ way to treat bone cancer. The most effective management of canine osteosarcoma involves incorporation of a multimodal therapy to address the primary tumor and metastatic disease.11 Listed below are options that may be right for you and your pet.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy delivered by a linear accelerator can be used to treat cancer-related bone pain.1 This treatment is for alleviating pain and is not curative. The intent is to provide a good quality of life and to provide pain relief when amputation is not an option. Radiation therapy is usually combined with pain medications and is generally effective in reducing symptoms quickly in the majority of dogs and without significant side effects. However, because anesthesia is required for the procedure, there are associated risks. Some dogs develop dryness and redness of skin and hair loss in the area to which radiation is delivered. This condition is referred to as radiation dermatitis and looks like a sunburn. Applying a veterinarian prescribed topical cream can help with this problem.3

As with all treatment choices, there are some disadvantages of radiotherapy. First, when pain is relieved in the tumorous limb, dogs will increase activity. This could lead to a pathologic fracture of the bone. Second, radiotherapy does not produce a positive response in some dogs. Third, radiation only targets the tumor in the bone and does not address distant spread. Usually, 1-4 doses of radiation are given in conjunction with home care and bisphosphonates depending on the protocol.3

Limb Amputation

The current standard of care for canine appendicular (limb) osteosarcoma is amputation of the limb followed by chemotherapy.16 Removal of the affected limb resolves the pain in 100% of the cases. Unfortunately, many people are reluctant to have this procedure performed due to misconceptions about the dog’s quality of life. While it is true that if a person loses a leg, they would be significantly handicapped unless they had a well fitted prosthetic. However, losing one leg out of four does not significantly restrict a dog’s activity level, even for the front legs of the giant breeds. After the recovery period for amputation is over, most dogs are running and playing as usual. It should also be remembered that dogs are not self-conscious about their image and the loss of a limb has no social ramification for them. It is more likely that his or her owner will need to adjust to the new appearance and not look at it as a disfigurement.

Surgically removing the affected limb also removes the primary tumor. It is clearly the fastest and most reliable way to end bone pain and to minimize complications of the bone tumor such as pathologic fracture. However, other factors such as concurrent orthopedic and neurologic disease need to be considered before deciding to sacrifice the limb. Amputation is major surgery and is not without risk of complications.

Limb-sparing Surgery

Limb-sparing techniques developed for humans have also been adapted for dogs.

To spare the limb and avoid amputation, tumorous bone is removed and a new technique called bone transport osteogenesis is used to promote new bone growth at the site. The joint nearest the tumor is fused so that it cannot be flexed or extended,22 and this procedure preserves limb function in over 80% of dogs. Again, surgery may be followed by complications such as infections which may occur in 30–50% of patients or implant failure which occurs in 20–40%. Another problem is tumor recurrence which appears in 15–25% of the cases. This technique is used more for dogs with special neurologic or orthopedic problems, but it may also be offered as a choice for owners who are not comfortable with limb amputation.18

Owners should keep in mind that grafting of new bone structure requires a significant amount of healing time and to seriously consider the fact that your pet’s life expectancy may be measured in months.20 Limb sparing cannot be done if more than 50% of the bone has been invaded by the tumor or if neighboring muscle is involved.22

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often used as a supplement to surgery to ensure that the disease has not spread into other areas of the dog’s body. In severe cases, limbs may need to be amputated to completely remove bone cancer.2 The median survival time with amputation alone is about three months, however, if chemotherapy is added to the treatment protocol, 10-20% of the dogs appear cancer free after one or two years. Unlike people, dogs tolerate chemotherapy very well and experience few side effects. Side effects do occur in a small percentage of patients and they include vomiting and diarrhea or infection due to a decrease in white blood cells. If you notice any of these signs in your pet, seek veterinary care right away.

As an owner and friend, you and your doctor should agree that when treating osteosarcoma, the most important goals are relief of bone pain and re-establishing a good quality of life. Another is longevity. We know for a fact that chemotherapy extends the life of dogs suffering from long bone osteosarcoma.1 The most successful chemotherapeutic drugs include carboplatin and cisplatin. Carboplatin is more expensive, but safer and easier to administer. Carboplatin is given once every 3-4 weeks for a total of 4-6 treatments.16 Recently, implantable cisplatin chemotherapy has been used to treat dogs with osteosarcoma with encouraging results.3

Doxorubicin is sometimes used as well. A qualified veterinary oncologist is often the best source for making this choice since he or she will be able to discuss with you the newest chemotherapy protocols. The life expectancy of a dog with a properly identified and treated osteosarcoma varies greatly, but may be a year or longer. Considering that large dogs live approximately 10 to 12 years, this is a significant extension of time for you and your pet to share.

Bisphosphonates

These bone-hardening drugs were originally used in human medicine to strengthen weak menopausal bone or to treat osteoporosis. Their use has evolved to treat bone pain in dogs, especially pain originating from bone cancer.1 Bisphosphonates act by inhibiting bone destruction which, in turn, helps control bone damage and pain caused by the bone tumor. Pamidronate, a strong pain reliever, is the most common bisphosphonate used in dogs;16 however, zoledronate, a new drug, is gradually becoming the drug of choice. Newer studies have a shown that zoledronate may also slow metastasis when given daily. In a small number of studies, zoledronate extends survival to one year even if the dog has not had surgery. The drug is well tolerated and when combined with surgery, it could potentially provide a more favorable outcome for dogs with osteosarcoma.16

Without therapy, the average survival time for most dogs is approximately two months. Most often the extraordinary pain associated with the primary tumor is too much for the dog and owner to bear. Amputation alone results in average survival times of approximately 4-6 months17 and a small percentage of patients (2%) will be alive after two years.18 If amputation was the only treatment applied, 72.5 % of dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma died or were euthanized because of metastases after 138 days from diagnosis.18 In contrast, combining amputation with chemotherapy extends the survival time to a little less than one year with 20% of the dogs still enjoying a good quality of life two years after surgery. Dogs undergoing limb-conserving surgery and chemotherapy experience the same survival time as dogs having amputation and chemotherapy.17

The most common cause of death associated with osteosarcoma is lung metastasis.16 Dogs with stage III osteosarcoma have a poor prognosis, with the median survival time amounting to about 76 days.18 Although osteosarcoma does not usually invade lymph nodes, if the cancer does metastasize to the lymph nodes, the survival time is reduced to 48 days. This is significantly shorter than dogs without metastasis in their lymph nodes who may live for another 318 days or more.18