Hemangiosarcoma

Hemangiosarcoma is a cancer that arises along the inner layer of cells lining blood vessels, lymph nodes and heart. These tumors are aggressive malignancies and due to rapid growth in blood vessels, they are often associated with sudden internal bleeding which can be life-threatening for your dog. If this tumor is located on a visceral organ, it can metastasize so rapidly that the cancer may be widespread before you notice any signs of illness in your dog.4 Unfortunately, there is no specific methods to provide early diagnosis of hemangiosarcoma.

The severity of hemangiosarcoma depends on location. If it is found on the skin’s surface, it may be curable, but if the tumor is detected on the internal organs, it must be completely removed in order to ensure a favorable prognosis. Hemangiosarcoma is diagnosed using X-rays and ultrasound followed by exploratory surgery using fine-needle aspiration of fluid accumulations and/or tissue biopsy of the mass.4 Once diagnosed, surgery can be done to remove the tumor. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are sometimes recommended depending on the stage and cancer subtype. Prognosis is highly variable, ranging from 1 month to more than a year. The average survival times with surgery and chemotherapy are a little more than half a year.

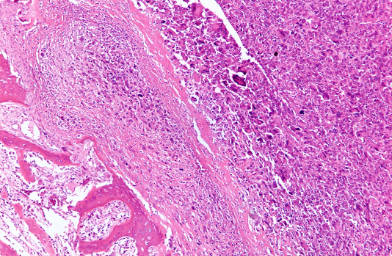

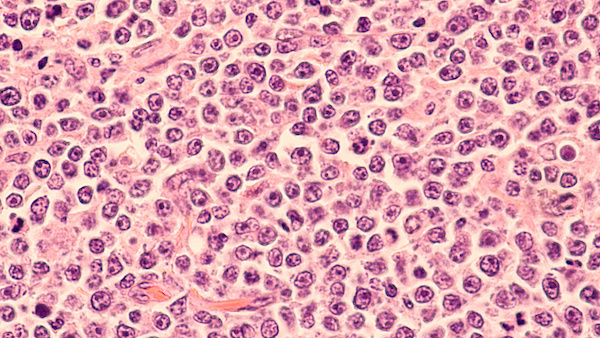

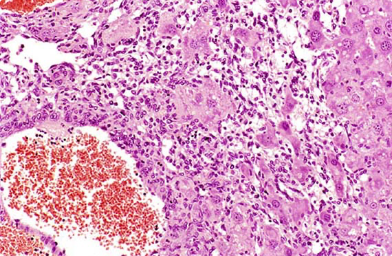

Hemangiosarcoma is an aggressive, malignant growth of cells lining blood vessels which occurs almost exclusively in dogs. The term “hem” refers to blood, “angio” refers to vessel, and “sarcoma” refers to tumor.1 Hemangiosarcoma can theoretically originate in any tissue since it involves blood vessels; however, it is most often found in skin, heart, spleen or liver. The skin forms of hemangiosarcoma are the most easily removed surgically and are often completely cured. The disease can also be referred to as angiosarcoma or metastatic hemangioendothelioma, the latter term reflecting its origins in the endothelial cell lining of blood vessels.2

Canine hemangiosarcoma accounts for approximately 5 to 7% of canine cancers but is one of the most common types of metastatic cancers found in dogs. It is more often seen in large breed dogs after middle age (6-13 years).3 Although there is no confirmed genetic component, Doberman pinschers, German Shepherds, Golden retrievers, and Labrador retrievers are more likely to develop visceral hemangiosarcoma.4

Once these tumors establish, they can spread rapidly throughout the vascular system. They often appear as tissue masses on the surface of the skin or on various internal organs. Hemangiosarcomas have a tendency to fill with blood, rupture, and lead to internal and external bleeding.

There are three types of hemangiosarcoma.4

- Dermal – Found on the skin.

- Subdermal – Found under the skin.

- Visceral – Most often found on the spleen, pericardium and the heart. Less frequently, it is found on kidney, liver or lungs.

Dermal and Subdermal Hemangiosarcoma

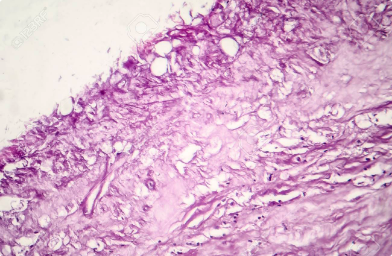

These types of cancer occur in approximately 13-15% of the cases and are most often associated with sun exposure.3 They are likely to form on non-haired or sparsely-haired skin such as the abdomen. Short-haired dogs with light-colored fur are at risk for the disease with dalmatians and pit-bulls being most vulnerable.

Skin hemangiosarcoma is felt as a lump in or under the skin which may ulcerate and bleed. Dermal hemangiosarcoma appears as a rosy red or possibly black growth on the skin; whereas subdermal growths may appear as a dark red blood mass under the skin. Skin hemangiosarcoma can be surgically removed and has the most potential for a complete cure. However, attend to any abnormal growth as soon as you notice it. If left untreated, approximately 30% of dermal and 60% of subdural hemangiosarcoma will spread and result in visceral malignancies.6

Visceral Hemangiosarcoma

These tumors occur primarily in the spleen (40-50%) and heart (10-25%).3 Although the spleen plays an important role in blood and lymph function, this relatively large organ is not essential to life.6 Both splenic and heart growths have the potential for breaking open and bleeding profusely. If a splenic mass is detected, tests will be performed in order to determine whether it is benign or malignant. If malignant, a complete removal of the spleen (splenectomy) is performed. Although this ends the potential for a life-threatening bleed, splenic hemangiosarcoma often spreads rapidly and it is likely that the tumor has already metastasized. For example, 25% of dogs with splenic hemangiosarcoma also have heart-based tumors.2 A sudden bleed in a heart-based hemangiosarcoma often fills the pericardial sac surrounding the heart and places an extraordinary pressure against the heart muscle itself. This prevents the heart from filling and pumping blood; the resulting pericardial effusion must be treated immediately.6 Although the visceral form of hemangiosarcoma is most often malignant and fatal, some success with regard to extending your dog’s lifespan has been attained using a combination of chemotherapy and surgery.7

Since hemangiosarcoma most often develops in visceral organs, it rarely shows clinical signs until the tumor has become enlarged and has metastasized. Even dogs harboring large tumors may show no signs or evidence that they have a life-threatening disease. Typically, clinical signs are often only observed after the tumor has ruptured and hypovolemia (a state of decreased blood volume or diminished body fluid) has occurred due to excessive bleeding. Common clinical signs of visceral hemangiosarcoma include:2

- Visible bleeding, including nosebleeds

- Pale colored gums

- Sudden weakness and short-term lethargy

- Swelling in abdomen

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Breathing difficulty

- Collapse

- Sudden death

In addition, an enlarged abdomen is often seen due to severe internal bleeding (hemorrhage). Affected dogs may show different symptoms depending on the amount of blood lost, and certain symptoms are transient since dogs reabsorb the blood components and make new blood cells. Clinical signs often recur.

The cause of this disease is not known. However, an almost exclusive occurrence in dogs and increased frequency in certain breeds indicate that heritable factors are involved. Genetic contributions have not been identified, but exposure to vinyl chloride has been associated with hemangiosarcoma. The rarity of this disease even in humans has dampened research efforts so that information with regard to causes is lacking. The only known cause is direct exposure to sunlight which is generally believed to be the cause of dermal hemangiosarcoma.2

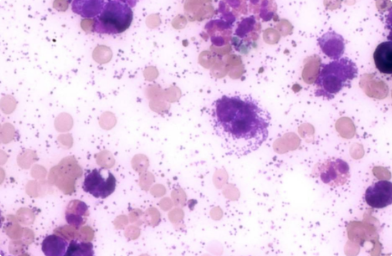

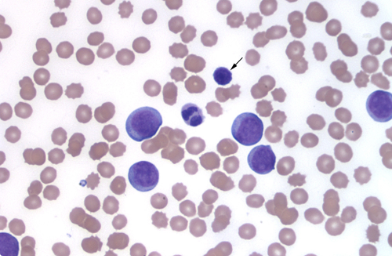

Diagnosis starts with a basic physical examination to evaluate your dog’s health. This includes examining mucus membranes for potential anemia (pale gums), feeling for abdominal lumps or swelling, drawing blood to determine if your dog is properly forming clots, and aspirating fluid to see if there’s any blood in the abdomen.6

Further diagnostics will include a complete blood cell count to determine anemia or low platelet count, chemistry panel, and urinalysis. Additional tests allow your vet to determine whether metastasis has occurred and the extent of organ involvement (canine cancer). X-rays or CT-scans of the chest and abdomen can be used to detect growths, abnormal fluid accumulation or masses in the lung. Abdominal ultrasound can help to reveal tumors in the spleen or liver. Echocardiograms provide information with regard to spreading of tumor to heart.2

A more accurate diagnosis will then depend on a tumor tissue biopsy. However, this can become exceedingly difficult since the most accurate results come from a biopsy of the primary tumor. Hemangiosarcoma is prone to spread; therefore, when multiple tumors are detected, it can be extraordinarily difficult to determine which is the primary tumor. Moreover, there is a significant risk for hemorrhage during or after these surgical procedures.6 There is currently no perfect blood screening test for detecting hemangiosarcoma.

Staging

Results from the various diagnostic tests can be used to stage the tumor and provide a basis for making treatment decisions. Two different three-stage classifications are used depending on whether the hemangiosarcoma tumor originates in skin or in an internal organ.3

Dermal / Subcutaneous Hemangiosarcoma

- Stage I: Primary tumor confined to the dermis

- Stage II: Primary tumor involving the hypodermis with or without dermal involvement

- Stage III: Primary tumor with underlying muscular involvement

Visceral Hemangiosarcoma

- Stage I: Localized tumor; no other tumors seen in imaging or at time of surgery

- Stage II: Ruptured tumor confined to the primary site, with or without metastasis present near the primary tumor

- Stage III: Ruptured primary tumor with invasion into adjacent structures plus local or distant metastasis

Treatments will vary depending on the location of the hemangiosarcoma and the extent to which it has metastasized. Most hemangiosarcoma of the skin can be removed surgically; however, if the vet is unable to remove the skin hemangiosarcoma completely or suspects that cancerous cells have spread locally to the muscles or subcutaneous tissue, chemotherapy or radiation therapy may also be employed.2 There are no known cures for visceral canine hemangiosarcoma, but there are treatments that can potentially increase survival and prolong your dog’s quality of life.8

Surgery

Surgery is the primary method of treatment for all dogs with hemangiosarcoma. Dermal tumors are relatively easy to find and many are curable with surgery alone. Your dog’s affected tissues will have to be removed, and in some cases, a large area will have to be cut out. Visceral forms of hemangiosarcoma are much more difficult to treat and require more aggressive procedures. With splenic hemangiosarcoma, it is possible to remove the entire spleen as long as the tumor has been identified early, this is usually quite successful in suppressing the disease. Your pup’s life may also be extended if a heart tumor is found since surgical removal and/or a “pericardial tap” can be used to remove fluid build-up around the heart. Dogs undergoing this surgery are susceptible to irregular heartbeats. During surgery, your vet will examine the dog’s entire abdomen and potentially take biopsies for further analysis. With visceral hemangiosarcoma, success is more likely if surgery is used in conjunction with chemotherapy.7

Chemotherapy

The disease is highly metastatic, and chemotherapy is almost always recommended after surgery. The standard recommended chemotherapy protocol for hemangiosarcoma typically consists of the cytotoxic drug, Doxorubicin (Adriamycin, DOX), given intravenously (IV) once every 3 weeks for a total of 5 treatments. Side effects may be experienced by some dogs, typically within 2-5 days following treatment, and may last for up to a week. The most common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Rarely, the patient may develop cardiac toxicity if the drug kills too many normal cells around the heart.9

A newer method of drug administration, called “Metronomic” chemotherapy, has been used to reduce negative side effects while increasing the efficacy of the treatment. The method involves a low dose of a chemotherapeutic drug, such as cyclophosphamide, administered more frequently with a reduced number of rest periods. This approach has been shown to be generally tolerated very well. Although it does not completely destroy tumor cells, it does reduce the rate of new blood vessel formation necessary for local tumor growth which prevents expansion and may slow down metastasis.1

Immunotherapy

Patients treated with a new form of immunotherapy involving liposome-encapsulated muramyl tripeptide-phosphatidylethanolamine (L-MTP-PE) have shown a significant improvement. Although this drug is not available in the US, it is being used in the EU for treatment of pediatric osteosarcoma and has gained orphan drug status.10

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy (RT) is not used very often in cases of hemangiosarcoma. It is sometimes used in conjunction with chemotherapy to reduce pain and potentially prolong survival times in cases where an organ is involved. However, a recent study demonstrated that RT can indeed provide clinical benefits for dogs with hemangiosarcoma.11 RT can be used alongside chemotherapy and, on average, dogs have survived three-to-six month following surgery.8

If the disease is diagnosed early, surgical removal of the tumor can prevent its spread and your dog could still enjoy many happy years. However, the disease is usually quite advanced by the time symptoms appear and the prognosis is not very promising.

Average survival times with surgery and chemotherapy are approximately 6-8 months, with about 10-15% of dogs surviving for one year or longer with durable remissions. With surgery alone, most patients survive 1 to 4 months, however with no treatment, survival is less than 30 days. If treatment is not an option, euthanasia should be considered to prevent your dog from suffering through an internal bleed.5

Even with surgery and chemotherapy, the disease is likely to progress as the cancer cells continue to metastasize. Hemorrhages may occur from each new hemangiosarcoma which may cause transient weakness until the bleeding stops. If the bleeding does not stop, the patient will begin to show signs of shock and collapse.