Lymphoma

Lymphoma is a cancer that targets lymphocytes, white blood cells that originate in bone marrow and migrate to lymphoid tissues such as thymus, lymph nodes, and spleen.3 Since lymphocytes circulate in the blood, malignancies can also be found in other tissues, particularly in the liver and kidney.8 Lymphocytes play central roles in the immune system’s ability to fight off infection and their abnormal growth and division is often first detected in the lymph nodes.

Lymphoma is one of the top five cancers diagnosed in dogs.1 It represents 7-14% of all canine cancers2 and consists of more than 30 subtypes. Depending on the subtype, lymphoma can progress rapidly and become acutely life-threatening or be managed as a chronic disease. Canine lymphoma generally does not cause pain unless the bones are involved, and a definitive diagnosis is only reached after using multiple diagnostic tests. These include blood tests, fine needle aspirates of the tumor, biopsies, X-rays, and ultrasounds.

Making a decision about what to do for your beloved pet following diagnosis is difficult. However, with a complete evaluation of all test results and with the age of your dog and your dog’s overall health in mind, the veterinary oncologist will suggest a treatment. Protocols that include a combination of drugs usually achieve the highest remission rate and extend survival time.9 The most common chemotherapeutic treatment protocol for dogs with lymphoma is a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, L-asparaginase and doxorubicin.10 In the following sections, we hope to help you understand different subtypes, their symptoms, and corresponding treatment options so that the choice will be less stressful.

Lymphoma (also called lymphosarcoma or malignant lymphoma) is a diverse group of cancers that are derived from lymphocytes, white blood cells that originate in the bone marrow. Lymphocytes then migrate from their source to the thymus and other lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes and spleen. Although lymphoma is most often found in these lymphoid tissues, it can also develop in other tissues of the body since lymphocytes freely circulate in the blood.3 Tissues are constantly exchanging fluid with the blood, yet some of the excess fluid is drained off by vessels belonging to the lymphatic system which is a one-way network of branching vessels that empty into the heart. The lymphatic system is part of the immune system and numerous lymph nodes are located along its route which, in part, explains why the disease is often detected first in the lymph nodes8 Lymphoma can be deadly for dogs, especially those forms which progress rapidly and become life-threatening if left untreated. Other forms progress very slowly and are managed as chronic non-threatening diseases.

It is important to be aware of changes in your pet’s vitality and health since without diagnosis and treatment, the cancer can be aggressive and lead to a high mortality rate. The average dog with lymphoma only lives for approximately 30 days after diagnosis if no treatment is initiated. Fortunately, once the disease is diagnosed, it is generally quite responsive to chemotherapy and most people are very pleased with their pet’s quality of life during treatment.

Lymphoma is classified into low- and high-grade types. Of the two, high-grade is the most similar to Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in humans and is the most common form in dogs. It starts in the lymph nodes but can spread to other organs or the bone marrow. Dogs with this type of lymphoma often present with painless enlargements of their lymph nodes, and 20-40% of dogs will also have a history of weight loss, lethargy, and anorexia. This type of lymphoma usually affects the B-cell lymphocytes. Actually, this would be good news for the pet owner, since B-cell lymphocytes respond better to chemotherapy. In fact, when the best multi-agent chemotherapy protocols are used, 90% of dogs respond positively.

Classification can also be made based on location of cancer development. The four location types are multicentric, mediastinal, gastrointestinal, and extranodal.

Multicentric: affects external lymph nodes.

Gastrointestinal (alimentary): targets the stomach and/or intestines.

Mediastinal: involves organs within the chest, such as lymph nodes or the thymus gland.

Extranodal (cutaneous): affects the chest, skin, liver, eyes, bone or mouth.

- Roughly 80-85% of lymphomas in dogs are multicentric4; whereas, gastrointestinal lymphoma is diagnosed in only 10% of lymphoma cases7. The other types are very rare.

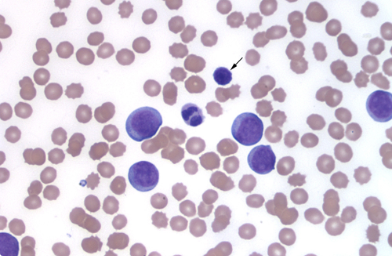

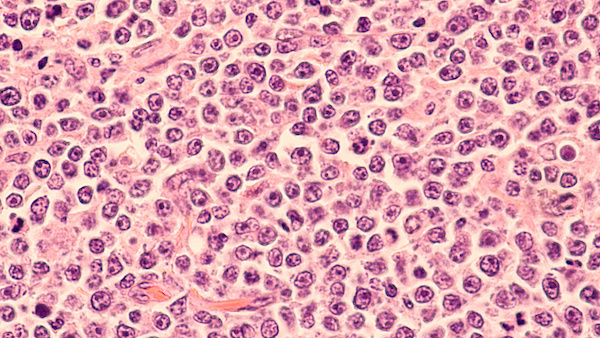

- In addition to the location of cancer development, further classification of lymphoma can be based on whether it involves B-cell lymphocytes or T-cell lymphocytes. Most lymphomas (70%) are of the B-cell subtype4 and the good news is that approximately 90% of dogs with B-cell lymphoma respond well to chemotherapy. In fact, about 50% of those dogs will stay in remission for one year, and 20-25% up to 2 years. Many can achieve remission a second time if the dogs have relapsed, especially if the drugs have been effective in the past. In contrast, only 40-60% of dogs with T-cell lymphoma will respond to chemotherapy, and about 50% of these dogs will stay in remission for 6 months

GENERAL SYMPTOMS

Specific symptoms of canine lymphoma will vary depending on cancer location, type of lymphoma, stage of the disease, and overall health of the dog. The variability in these characteristics can make the disease difficult to diagnose at first, but with that said, pet parents should be aware of the general symptoms associated with lymphoma.8 Be on the look out for the following symptoms.

- Lack of appetite.

- Weakness.

- Swollen lymph nodes under the jaw, in front of the shoulders, or behind the knee.

- Swelling of the legs or face.

- Excessive thirst.

- Excessive urination.

- Lethargy.

When examining your pet’s lymph node, you may feel a hard, rubbery lump under the dog’s skin which is generally not painful to the dog. Be aware that lymphoma may also affect lymph nodes that are not visible from outside the body, like those found inside the chest or in the abdomen. Be on the alert for other symptoms such as swellings, excessive thirst and frequent urination if you suspect your pet is not well.

SPECIFIC TYPES

Multicentric lymphoma

Multicentric lymphoma is by far the most common type of lymphoma in dogs and represents about 80 to 85% of diagnosed cases. In the majority of cases, the most obvious clinical manifestation is the rapid enlargement of lymph nodes.3 Additional symptoms are as follows:

- Lethargy.

- Fever.

- Anorexia.

- Weakness.

- Dehydration.

Gastrointestinal (Alimentary) lymphoma

Lymphomas developing in the gastrointestinal tract are the second most common form. These alimentary lymphomas, which account for less than 10% of canine lymphomas, mainly target the intestines. Typical symptoms are as follows:

- Vomiting.

- Diarrhea, often very dark in color and very foul-smelling.

- Weight loss.

- Lethargy.

- Lack of appetite.

- Malabsorption.

Mediastinal lymphoma

This form of lymphoma affects lymph nodes in the chest and is quite rare. In this disease, either or both the thymus and the mediastinal lymph nodes become enlarged in the area of the chest. Unfortunately, mediastinal lymphoma involves the high-grade malignant T-cell lymphocytes.3 Typical symptoms are as follows:

- Difficulty in breathing.

- Irregular heartbeats.

- A large mass in the chest region.

- Buildup of fluid in the chest.

Extranodal (Cutaneous) lymphoma

Extranodal lymphoma in dogs refers to lymphoma that targets a specific organ outside of the lymphatic system such as the skin, eyes, kidneys, lungs, or central nervous system. The most common extranodal lymphoma affects skin and is called cutaneous lymphoma.3 Typical symptoms are as follows:

- One or more lumps on skin or mouth.

- Dry and/or red patches of skin.

- Ulcers on the skin’s surface.

- Large tumors may also develop on the skin.

- Early stages of cutaneous lymphoma may be misdiagnosed as periodontal disease or gingivitis since they share multiple symptoms.

Currently, medical experts do not know what causes lymphoma in dogs. Viruses, bacteria, chemical exposure, and physical factors, such as strong magnetic fields, have been suggested as possible causes.9 Certain viral cells with properties similar to retroviruses have also been detected in short-term cultures of canine lymphoma tissue;8 however, viral causes for a lymphoma tumor have not yet been confirmed.

Similar to lymphoma in people, it is suspected that homes exposed to high levels of chemical use such as paints and solvents contribute to the onset of the disease. Moreover, suppression of the immune system, a known risk factor for the development of lymphoma in humans, could be a link between a weak immune response and lymphoma in dogs. Changes in the normal structure of chromosomes in canine lymphoma have also been reported; but again, causes have not been clearly established.9

RISK FACTORS

Although dogs of any age can develop lymphoma, the disease mainly affects middle aged to older dogs with a median age of six to nine years. Sex appears to be irrelevant, but it is generally agreed that neutered females tend to have a better prognosis.8 In terms of breed, any breed can develop lymphoma, but it is more prevalent in breeds such as Boxer, Scottish terrier, Basset hound, Airedale terrier, Chow chow, German shepherd, Poodle, St. Bernard, Bulldog, Beagle, Rottweiler and Golden retriever. Golden retriever is especially susceptible to developing lymphoma, with a lifetime risk of 1:8.4 Dogs with a lower risk include Dachshunds and Pomeranians.

Once cancer is a suspected, your veterinarian will perform a complete physical examination on your dog. Canine lymphoma generally does not cause pain unless the bones are involved, and a definitive diagnosis is only reached after using multiple diagnostic tests. These include blood tests, fine needle aspirates of the tumor, biopsies, X-rays, and ultrasounds. Which tests are performed depends on tumor location, but usually a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and urinalysis will also be recommended.4

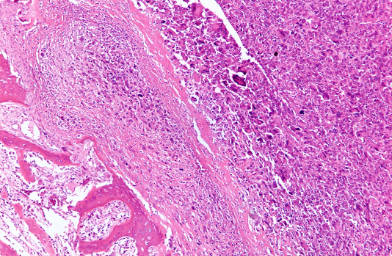

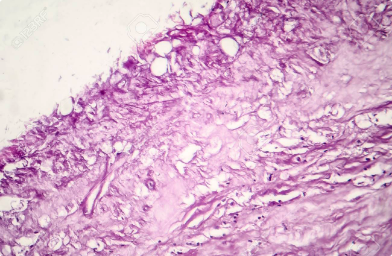

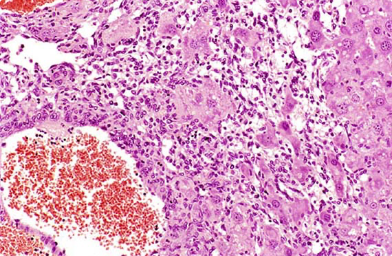

It’s generally agreed that a biopsy is the best way to diagnose lymphoma. A biopsy is a minor surgical procedure which is used for accuracy of diagnosis.4 The most common method is the incisional wedge biopsy which involves the removal of a piece of tissue from the lymph node. The other method is excisional biopsy which requires the removal of the entire lymph node. In addition to the biopsy, more specific testing may be required for a confirmatory diagnosis. In this case, diagnostic imaging, including X-rays and ultrasound, will be used to evaluate the size of regional lymph nodes, and bone marrow samples will be sent to a veterinary pathologist to determine the extent of disease.6

If the diagnosis indicates that your dog has developed lymphoma, your veterinarian will begin additional testing in order to formulate a treatment. Testing may include the following techniques:4

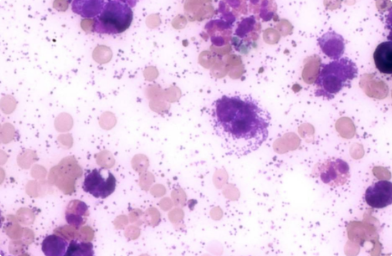

- Immunochemistry: identifies whether your dog has developed B-cell or T-cell lymphoma. This information is vital for providing an informed diagnosis.

- Flow cytometry: another test used by veterinarians to distinguish between B-cell or T cell lymphoma.

The stage of the disease is also important for appropriate treatment and accurate prognosis.5 Some veterinarians recommend “staging tests” following a lymphoma diagnosis to determine how far the disease has progressed throughout the dog’s body;2 staging of dogs has been standardized by the World Health Organization and the stages are defined as follows:4

Stage I: Single lymph node involved.

Stage II: Multiple lymph nodes in the same region involved.

Stage III: Multiple lymph nodes in multiple regions involved.

Stage IV: Liver and/or spleen involved (may or may not have lymph node involvement).

Stage V: Bone marrow, blood involvement and/or organs other than liver, spleen and lymph nodes involved.

There is no cure for this disease, and relapses are common after remission. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are routinely used for lymphoma treatment in animal patients;6] however, chemotherapy is often the most effective treatment. Recent evidence suggests that modifying your dog’s diet can reduce the growth of cancer cells.7 Ask your veterinarian about this.

After a complete evaluation of all test results and with the age of your dog and your dog’s overall health in mind, the veterinary oncologist will suggest a treatment protocol. Often it involves the use of chemotherapy alone or combined with radiation therapy.6 Of course, the type of chemotherapy your vet recommends will vary depending on the type of cancer. Protocols that include a combination of drugs usually achieve the highest remission rate and extend survival time.9 It should be remembered that lymphoma is a systemic disease, and surgery and radiation are usually not the most effective options for treatment. However, in some cases, they may also be recommended.2 The most common chemotherapeutic treatment protocol for dogs with lymphoma is a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, L-asparaginase and doxorubicin.10

Other chemotherapy drugs such as chlorambucil, lomustine (CCNU), cytosine arabinoside and mitoxantrone, are also used for lymphoma treatment but not as frequently. In most cases, appropriate treatment protocols cause few side effects, but white blood cell counts must be monitored.5 Most dogs are able to tolerate chemotherapy quite well–in fact, much better than humans typically do. Some will get sick from chemo, but serious side effects are uncommon. For example, dogs rarely lose their hair—with the exception of, but not limited to, Poodles, Old English Sheepdogs and the Bichon Frise.

Fewer than five percent of dogs treated with chemotherapy for their lymphoma will experience side effects that require further hospital treatment. Most dogs experience a partial or complete remission of their cancer following treatment, and side effects are usually not severe. These side effects may include loss of appetite, lethargy, and mild vomiting or diarrhea that persists for a day or two. If these side effects get more severe, it’s important to seek further treatment.4

Unfortunately, the life expectancy for a dog with lymphoma that has reached Stages III through V is about four to six weeks, and drugs are not likely to prolong their lifespan. They can, however, be given medication to reduce swelling and improve their quality of life at the end.3 If the disease is diagnosed early however, the prognosis is much more positive.

Complete cure is rare with lymphoma and treatment tends to be palliative, but long remission times are possible with successful chemotherapy. With effective protocols, the average first remission times are 6 to 8 months, although, second remissions are shorter and harder to accomplish. Overall, chemotherapy is beneficial for most dogs diagnosed with lymphoma, and the average survival time is 9 to 12 months.5